Introduction

In China, the term “leftover women” generally refers to unmarried women over the age of twenty-seven, who often face significant pressure in finding a husband. To ensure their daughters get married as soon as possible, and avoid them becoming “leftover women,” parents have developed marriage markets, where they can find “suitable” matches for their daughters. These are held in public parks within major cities, with the tacit endorsement of the Chinese government. In one of China’s hottest marriage markets, however, the Shanghai Marriage Market, a series of controversies have erupted during the past several years. The first of these, in 2015, saw artist Guo Yingguang stage an alternative matchmaking scenario in the Shanghai Marriage Market as part of a performance project, through which expressed her opposition to the term “leftover women” and to the traditional ideals perpetuated by the marriage system more broadly. In 2016 meanwhile, cosmetics company SK-II also staged a Marriage Market “takeover” in People’s Park, accompanied by a short film that featured testimonials from women describing the social pressures of being a “leftover woman.”1 As these two specific case studies demonstrate, between 2015 and 2016 various different actors, including parents, artists, entrepreneurs, and the wider public, began to engage in debate over the definition of “leftover women,” leading to reflections on gendered power relations, as well as the dynamics of spatial occupation, intervention, and competition that shape the Shanghai Marriage Market.

In urban China, urban development is often a state-led project and spatial practices are perceived as forming part of a wider project for consolidating the state’s authority and maintaining social stability.2 As a consequence, urban space often reflects dominant social norms and gender representations. In recent years, however, more critical attention has been paid to the possibility of alternative practices, with scholars exploring the various ways in which women as well as queer cultures have attempted to construct their own social spaces and actively engage in cultural resistance.3 As the ongoing debates around “leftover women” in the Shanghai Marriage Market attest, gender representations in China are becoming increasingly unstable and contested, at the same time that spaces are being continually (re)constructed in a way that mirrors the shifting dynamics of contemporary gender relations.4

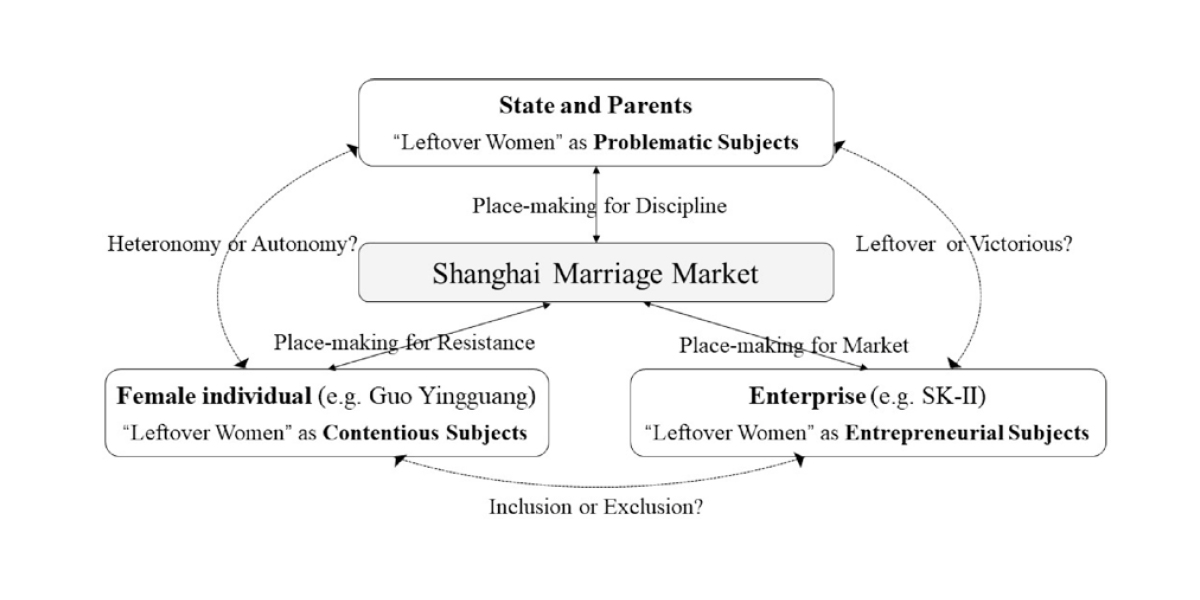

Using “place-making”—understood as a socio-material process of creating and re-creating geographies, involving the intervention of different actors and networked and relational politics—as an analytical perspective, the following section specifies three different logics of place-making in the Shanghai Marriage Market, further exploring the politics of women’s representation and the power relations behind it.5

The representation of “leftover women” and place-making of the Shanghai Marriage Market

Making a place for discipline: marriage market led by the state and parents

In China, urban women often face marriage pressure for two reasons. Firstly, in the traditional Chinese marriage system, parents must arrange for their daughters’ marriages when they reach marriageable age. Secondly, with the Chinese government’s introduction of the one-child policy in the 1980s, the bond between parents and children has become stronger, which has increased parental involvement in their daughters’ marriages. In addition, and with the rapid increase in the cost of living in urban areas after the 1990s, parents prefer their daughters to marry into better-off families that will enable them to live a secure life.6 In short, traditional culture, together with policy revisions and economic pressures, have led to parents being particularly invested in their daughters’ marriages.

As the official Chinese media outlet, People’s Daily suggests, “the personal marriages of hundreds of millions of young people are actually a national matter.”7 This means that women’s marriages are also part of state governance. In the government’s view, too many unmarried women can lead to low fertility rates and a surplus of single men, which can cause a demographic crisis and social instability.8 Therefore, the government not only urges women to marry “on time” through its official media channels but also actively tries to organize various matchmaking events: back in 2007, Xinhua News published a hotly debated article on “Escaping Leftover Women Trap,” while the Shanghai government has held mass matchmaking fairs since 2011.9

The government and parents have also tried to define the concept of “leftover women” in order to identify women who are at risk of facing the problem of being “older and unmarried.” In 2006, the Chinese Ministry of Education first recognized “leftover woman” as a “new word in Chinese.” In 2007, the Chinese Women’s Federation defined “leftover women” as women over the age of twenty-seven, implying that women should preferably get married before this age.10 Notably, parents are also careful to present their daughters’ personal information in matrimonial advertisements to avoid their daughters being classified as “leftover women,” with keywords in advertisements: “26 years old, unmarried,” “160 cm tall,” “bachelor’s degree,” “civil servant,” and so on. Seemingly, in the parents’ view, women who are “not too old” and of smaller stature, as well as women who hold lower educational qualifications, and have stable career paths, may still be able to attract men’s attention, and thus escape being labeled as “leftover women.”11

Importantly, it is through the site of the marriage market itself that the discourse of “leftover women” by the government and parents plays its disciplinary role. The Shanghai Marriage Market, one of the earliest and largest marriage markets in China, is held in Shanghai People’s Park, with the active participation and support of members of the parent's generation. Moreover, it has become one of the few urban public spaces in Shanghai where free assembly is allowed, with the tacit approval of the government.12 Those who are most active in the Shanghai Marriage Market are generally the parents, who tend to arrive at the park early and lay claim to a portion of the public space, utilizing objects such as chairs and umbrellas to create a “stall” through which to market their daughters. The competition for marriage is thus accompanied by the competition for space. Usually, parents post their daughters’ personal information on the umbrellas in the hope of gaining attention from the man’s parents who are browsing the marriage market.13

In other words, the parents and Chinese state co-construct public perceptions of urban “leftover women” to regulate the marriage system in accordance with family ethics and state governance. Also, the dominant discourses play their disciplinary role by relying on the place-making of the Shanghai Marriage Market as led by the parents and government.

Making a place for resistance: Guo Yingguang’s performance art and cultural resistance

However, in recent years, more and more urban women have become dissatisfied with the marriage market and have begun to oppose their stigmatization as “leftover women.” A new identity begins to emerge that locates women’s value in independence and self-improvement, insisting that women should have the right to make decisions about their own marriages. As a result, acts of resistance have taken place in the marriage market.

In 2015, independent artist Guo Yingguang, herself still unmarried, decided to rebel against the marriage system. On her motivation, she said, “I’ve reached the age of so-called ‘leftover women,’ and my idea at that time was to fight against it. I was not against marriage, but against criteria for measuring happiness.”14 Beginning her resistance with a spatial intervention, she went to the Shanghai Marriage Market and launched a performance art project, “Marry for Myself,” with alternative personal information in the matrimonial advertisement:

Liaoning native. Only daughter. Master of Arts from a higher art institution in the UK. First-class honors degree. Independent personality. Funny and humorous. Both parents are intellectuals. 15

In the marriage market, matrimonial advertisements tend to first highlight the age of the woman, and parents often choose not to showcase their daughters’ merits, such as higher education, in order to avoid them being perceived as “leftover women.”16 In contrast, the advertisement designed by Guo herself not only doesn’t mention her own age but emphasizes what she considers to be more important values, such as her education, ability, and personality. Undoubtedly, this alternative advertisement challenged the dominant discourse constructed by the parents’ generation in the marriage market and was criticized by other parents on the scene. According to Guo:

All parents will first ask: “Why didn’t you write down your age?” After knowing my age, their response was, “You are too late.” They also questioned: “seeking marriage for yourself?” Some people were dissatisfied with my high education, “she got a master’s degree, but it was useless.” 17

Guo Yingguang documented her artistic actions in the marriage market and produced photobooks and short films to be exhibited around the world.18 Through the exhibition, more people were able to see the discrimination and prejudice women encounter in China’s marriage market, which Guo believed would drive change in the current system.19 It is clear that the marriage market is not only a place for the production of dominant discourses on “leftover women” by the state and parents, but also supports practices of resistance. Guo, for instance, does not shy away from the term of a “leftover woman,” instead deliberately presenting herself as one in her matrimonial advertisement. Thereby, the “leftover woman” becomes a contentious rather than problematic subject, as she is conventionally constructed by the government and parents. Guo’s resistance is also based on specific place-making practices, including critical spatial interventions and alternative representations of the marriage market through photography and video in exhibition.

Making a place for marketing: SK-II’s commercial advertising and brand marketing

In the wake of Guo Yingguang’s artistic action, reflections on the phenomenon of “leftover women” and the marriage market become a popular social issue. In April 2016, the cosmetics company SK-II released a short film, Marriage Market Takeover, which was filmed on location was in Shanghai Marriage Market. The film’s narrative, which tells the story of women’s resistance to the stereotypes associated with the “leftover woman,” revolves primarily around the conflict between parents and daughters. The director presents the parents’ anxiety about their daughters’ marriage and highlights the daughters’ response: “Although I am a ‘leftover woman,’ I am good at my job, I can be a victorious woman.” In the following story, the daughters go to the Shanghai Marriage Market to protest, displaying pictures of themselves dressed smartly and proposing new female values such as independence and personal struggle. The story ends with the parents being moved by their daughters’ photos and advocacy, reconciling with them and acknowledging that “leftover women are also honorable.”

However, unlike Guo Yingguang’s practice, the women’s resistance as it is presented in this short film is a fictionalized story that further serves the brand’s marketing. In fact, the “real” purpose of the film was to address the plight of SK-II’s declining sales in mainland China in recent years. Moreover, Marriage Market Takeover was just one of a series of short films SK-II had made since 2015, loosely grouped under the theme of “Change Destiny.” Interestingly, an earlier version of the theme was actually “Change the Destiny of Your Skin,” although this was later changed because the actress who participated in the shoot, Tang Wei, made the point that “changing your skin means changing your destiny.”20 In other words, in order to “change destiny, you must first buy SK-II cosmetics in order to “change your skin.” Also, the choice of “leftover women” and “marriage market” as the film topics were based on market research, after SK-II’s account director mentioned that their team found that many target consumers saw “leftover women” as a symbol of independence.21 The marketing campaign achieved great success and, within nine months of the film’s release, SK-II’s sales in mainland China had jumped by 50 percent.22 The brand’s President, Markus Strobel, emphasized that this was precisely because the topic of the “marriage market” appealed to consumers such as female executives.23

In other words, SK-II’s appeal to debates around “leftover women” who actively resist that label is also an appeal to “successful” entrepreneurial women, the same consumer base that constitutes their own target “market.” At the same time, the Shanghai Marriage Market, previously configured in Guo Yingguang’s practice as a site of resistance, is transformed in SK-II’s advert into a backdrop for commercial filmmaking. As a result, critical voices emerged after the release of this film, among them artist Lu Jingjing, who publicly criticized SK-II for limiting their depictions to middle-class and affluent women who already belong to a high-income bracket. She further questioned whether this meant that “leftover women” who could not afford SK-II cosmetics did not have the right to resist prejudice and stereotypes.24

Discussion and conclusion

As Judith Butler has made clear in her seminal book Gender Trouble, the representation and subject formation of women are controversial fields.25 This also holds true for “leftover women” who, in a marriage system led by the government and parental influence, become problematic subjects who are no longer favored in matchmaking. For artist Guo Yingguang, however, “leftover women” are contentious subjects with the potential to intervene in socio-political controversies and change the system. Ironically, in SK-II’s short film, the “leftover women” who dare to resist are reinterpreted as entrepreneurial subjects with spending power—an interpretation which has, in its turn, been criticized by other female artists.

At the same time, the political process of women’s representation is accompanied by the making and remaking of place. On the one hand, different actors occupy, intervene in, and transform urban space according to their own purposes—as seen in the spatial appropriation of Shanghai People’s Park by parents with the government’s acquiescence, as well as in Guo Yingguang’s artistic intervention, and in the commercial transformation of space by SK-II. On the other hand, the meaning and identity of place are also continually changing. While the marriage market serves as a space of consolation for parents to ease their anxieties about their daughters’ marriage, Guo Yingguang sees it as a site of resistance. In SK-II’s film, meanwhile, the marriage market is transformed into a symbol of middle-class women’s “changing destiny.”

It is worth noting that, clearly, Guo Yingguang’s artistic resistance has not entirely overturned the government and parent-led model of women’s representation and place-making. Today, the marriage market is still present in China’s major cities and continues to attract many parents. Likewise, the release of SK-II’s film does not mean that women’s resistance has become completely commercialized and lost its radical edge. Actually, there are women artists like Lu Jingjing who criticize the negative effects of commercialization on women’s resistance. In other words, the politics of women’s representation is an ongoing process of debate, which both configures and is shaped by the appropriation of, and competition for, space by different actors. Just as the government, parents, corporations, and female artists each claim different definitions of “leftover women,” each has a different strategy for placemaking in the Shanghai Marriage Market. Using place and space as perspectives, we also have the opportunity to examine gender issues in contemporary China more broadly, and to reflect on the unequal power relations behind them and the ensuing prejudice and discrimination.

Yimeng Yang is working on his double master’s degree offered by National Taiwan University, Leiden University, and the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS). His research focuses on urban politics and cultural/heritage governance, with China as an empirical case. He is also interested in the areas of rural development, gentrification, and critical tourism studies.