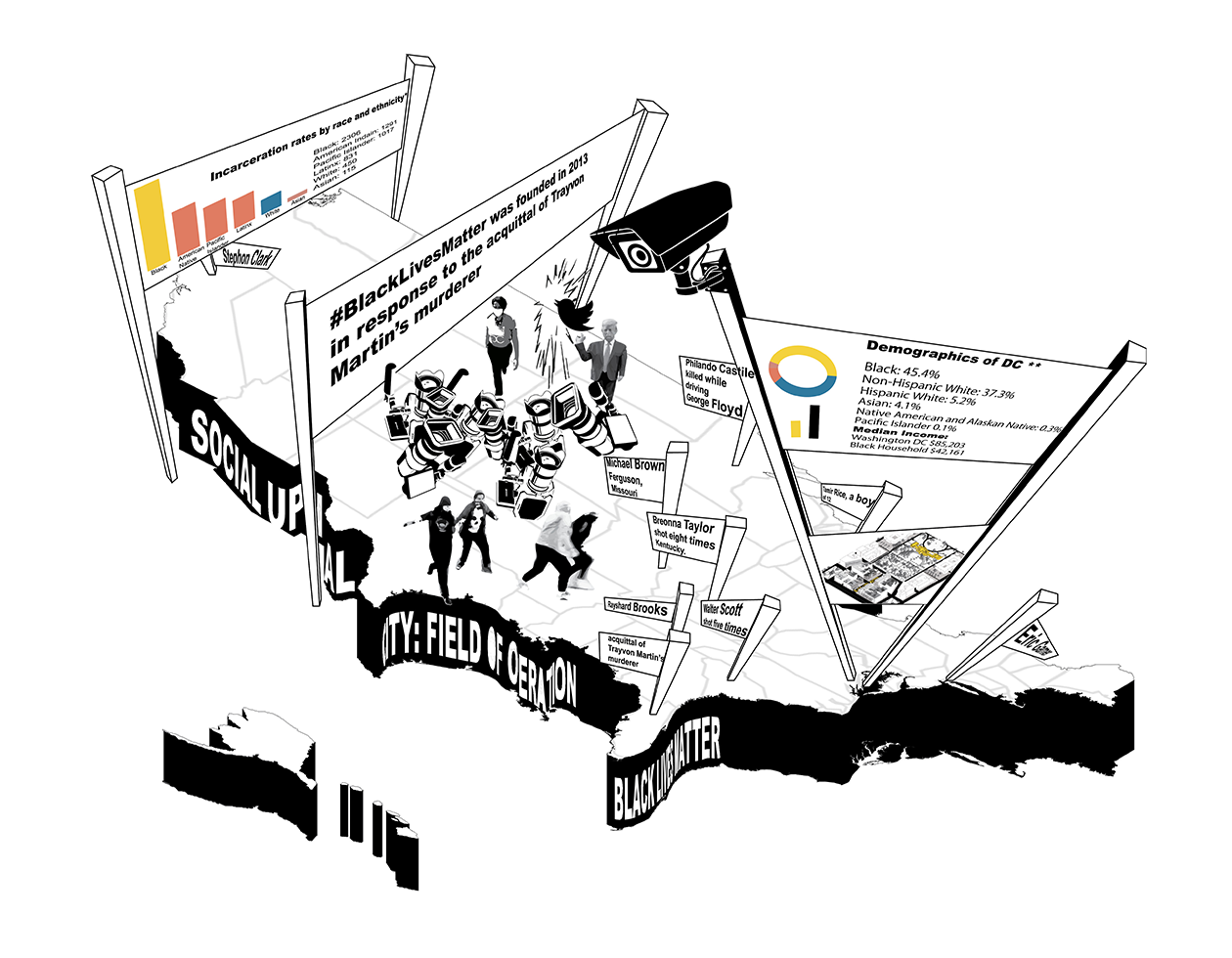

Black Lives Matter (BLM) was founded in 2013 in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer and a series of incidents of police brutality and racism, mainly in the United States.1 On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis while being arrested on suspicion of using a counterfeit $20 bill. Floyd’s death led to nation-wide protests over police brutality and systemic racism. On June 5, 2020, Washington, DC’s Department of Public Works invoked the words of the movement, painting “BLACK LIVES MATTER” across 16th Street NW. That same day DC’s mayor Muriel Bowser, the first Black woman ever to be re-elected to that office, announced that a portion of the street outside the White House would be renamed as Black Lives Matter Plaza. On May 11, 2021, the mural was temporarily removed due to underground electric infrastructure maintenance. It was repainted three days later.

This series of drawings is designed to portray the frictions among protesters, politicians, and mass media “bystanders” amid the social upheaval of racial justice protests, stress of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the 2020 US presidential election campaign. The occupation and renaming of the portion of 16th Street that runs directly in front of the White House set an unprecedented contested urban backdrop within a city that is also seen as the political epicenter of the US. Capturing the accumulating tensions among multiple constituencies and agents, the series of drawings aims to explore the active role of narrative in shaping the demographics of urban space and the subjectivity of citizenship.

The political instrumentalization of the mural commissioned by Mayor Bowser on 16th Street NW, the site of the current Black Lives Matter Plaza, puts certain realities into conversation: the agency of physical public space and its digital or online equivalent, and the balance of politics and social dynamics. The implementation of the mural remains controversial not only in a rhetorical sense, but when understood within its socioeconomic, political, and geo-spatial contexts. These drawings aim to compile interpretations from various points of view. Beyond its physical presence, what comes under scrutiny are the political connotations elicited by its urban setting and the insurgent occupations that reconstruct its urban identity.

Within the competing narratives a certain urban iconography is made evident—one that is constructed by vested interests and representational immediacy. The images that emerge from this particular instance are not only the fifty-foot-wide city-funded letters that run in front of the White House, but also the physical street sign signaling “Black Lives Matter Plaza,” erected by Mayor Bowser as part of the renaming process (i-5). At the same time, nearby St John’s Church becomes part of the iconographic array—this is where, minutes after police forces used tear gas to disperse a peaceful demonstration, former President Donald Trump famously staged his controversial photo op, posing with a bible in front of the parish house that caught fire as a result of the protests (i-4). These examples perpetuate the “negotiation of powers, rights, and vulnerabilities.”2

This sequence of illustrations draws on the dynamics of interpenetrating narratives—between media, reality, and social media—to unfold numerous stories at once. In doing so, the series attempts to visualize a “dynamic and responsive” commons that “unfolds events in time:”3 the mural, which mayor Bowser called an instrument for statements to be heard was labeled by the BLM DC protesters as “a performative gesture” (ii-3) and “a deviation from real policy change.”4 Tweets made by Trump accused Bowser of being “grossly incompetent”5 (ii-4), while religious organizations filed a federal lawsuit against her for the renaming of public space (ii-6), and BLM activists appended the original mural to say: “BLACK LIVES MATTER = DEFUND THE POLICE” (ii-7, 9).

The communicating apparatus of BLACK LIVES MATTER draws its theoretical basis from semiotics, in the way that its spatial forms, as signifiers, communicate with the ideology as signified.6 The three-word banner recalls a history of systemic inequality and bureaucratic regimentation inflicted upon Black Americans. The most ostensible and violent manifestation of this structural injustice is seen in the incarceration demographics and police violence statistics that populate the first illustration (fig. 1).

Graphically, the series uses the language of the mural itself—the yellow color of the letters and the dark asphalt texture—as the backdrop for presenting these simultaneous narratives (fig. 2). Notably, these very qualities have made the mural into its own kind of repeatable image, and ultimately its presence had a mimetic effect: it appeared on social media and other online spaces but also led to the creation of BLM murals in hundreds of cities worldwide, buttressing the sense of anti-racist solidarity.7

Finally, no detail in this series is exempt from narrative. Even the date is crucial. June 5—the day of the mural’s inauguration and the plaza’s renaming, reveals another connection: it is also the birthday of Breonna Taylor, the 26-year-old Black woman who was mistakenly shot and killed by police officers in March 2020.

The concerted struggle of the BLM movement brings into conversation the meaningful output of on-site physical information, the profuse interpretations and occupations of space, and media-generated narratives. These events interact with the sign—BLACK LIVES MATTER—in constant confrontation and juxtaposition, recalling the complex and politically and socially entrenched struggle of Black Americans.

Liu Yunsong is a student at Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) with the Mdes program. She holds a Bachelor of Architecture from Tsinghua University and a Master degree in Urban Design from University of Michigan. Her professional and school works unfold around the topics of activism and social equity in global south countries, embracing regulatory, environmental, and vernacular processes and matrix.