All cities are fictions. Their literal edges are nebulous, with their physical definitions being endlessly rewritten, but their boundaries come into focus as shared narratives. The fiction of a city weighs as much as its physical shadow. Such cities can exist on the network or exist as consensus. They are shaped like stories and coalesce around common practices or conditions of belonging. They are lived and occupied, read and watched with consequence and meaning. They are products of culture and, in turn, produce culture. The urban imaginary has always been a site to test out new scenarios and emerging cultures. In their speculative streets, we play out unexpected and unintended futures, along with their associated social and political ideologies. Whether it be speculation around the impacts of industrialization and mass production, the imminent arrival of driverless cars, seamless augmented reality, or artificial intelligence, these fictional worlds give form to our most wondrous technological possibilities and gravest concerns. The history of future cities is a chronicle of the hopes, dreams, horrors, and anxieties of the time in which they were made. They are the architectural and urban construction of ourselves, fraught with contradictions, encoded with the concerns of the present.

Following centuries of colonization, globalization, and never-ending economic extraction we have remade the world from the scale of the cell to the tectonic plate. Urban development has forever changed the composition of the atmosphere, the oceans, and the Earth. The Ecumenopolis, or planetwide city, has long been a narrative of science fiction. The term was conceived in 1967 by the city planner Constantinos Doxiadis to describe the hypothetical concept of total planetary urbanization. Among many others, the worldwide city has taken on the form of “The Sprawl” in William Gibson’s trilogy (1984-1988), a world without trees in Douglas Trumbull’s film Silent Running (1972), and Trantor, a planet made entirely from architecture in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series (1942-1986). As in fiction, our dystopian present has us already living in a planetary city, an unevenly distributed megastructure hiding in plain sight. There is no city and country anymore, no nature and technology. Instead, we have engineered a continuous urban construct that stretches across the entirety of the Earth. It was not master-planned by a single imperial power or a cyberpunk mega-corporation. It was slowly stitched together from stolen lands by planetary logistics, where landscapes have become resource fields, countries have become factory floors, the countryside has become industrialized agriculture, and the oceans have become conveyor belts. Architecture is a geologic force, and everything is urban.

But what if we radically reversed this planetary sprawl? What if we reached a global consensus to retreat from our vast network of cities and entangled supply chains into one hyper-dense metropolis, housing the entire population of the Earth? Seminal biologist Edward O Wilson describes his “Half-Earth” proposal as an “achievable plan“ to stave off mass extinction, by devoting half of the Earth’s surface completely to nature. For Wilson, the magnitude of the problem is far too large to be tackled with small gestures, and any solution must be commensurate with this scale and urgency. The byproduct of this global park, however, is the necessity to redesign the realities of the present-day planetary city.

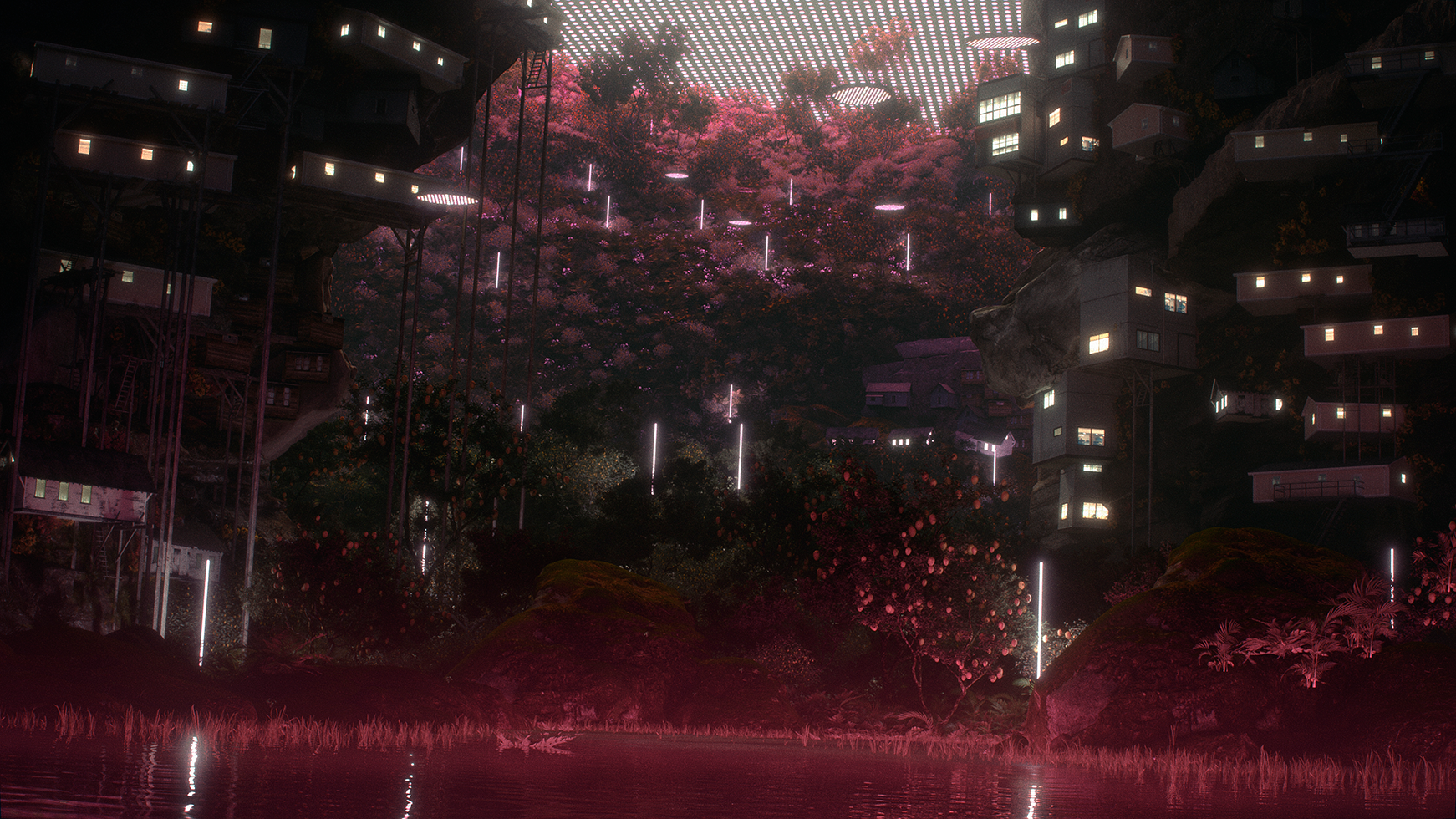

Planet City begins with this question and builds the story of another total urban fiction. Planet City is an imaginary city for 10 billion people, an exploration of extreme density, where we surrender the rest of the world to a global scaled wilderness and the return of stolen lands. In its most provocative form—reorganizing our world at the scale of our densest cities—Planet City could actually occupy as little as 0.02 percent of Earth.

Although wildly provocative, Planet City eschews the techno-utopian fantasy of designing a new world order. This is not a neocolonial master plan to be imposed from a singular seat of power. It is a work of critical architecture—a speculative fiction grounded in statistical analysis, research, and traditional knowledge. It is a collaborative work of multiple voices and cultures supported by an international team of acclaimed environmental scientists, theorists, and advisors. In Planet City we see that climate change is no longer a technological problem, but rather an ideological one, rooted in culture and politics.

This is a fiction shaped like a city. Simultaneously an extraordinary image of tomorrow and an urgent examination of the environmental questions facing us today.

Before dawn, thousands of autonomous cleaning blades squeak along the solar fields. Waves of mirrors ripple, as they rotate to chase the changing light—a billion panels collected from all over the world.

Vertical orchards weave through the city’s 160 floors. Between them, birds migrate across climate zones, while shepherds herd the harvest bots and nomadic neighborhoods follow the patterns of fruit blooms.

We are not precious about where we get our light. A synthetic sun casts purple shadows, while still warming the skin and fertilizing the soil. In the lower reaches, nature hums and crackles with the sound of flickering LEDs—sunrise over a new kind of wild.

The batteries of Planet City are alive with fish and algae, as excess wind and solar power pump water through canals to high altitudes, holding lakes in the city’s upper floors. When needed, the dams open and turbines turn. Tides rise and fall, as lights glow, televisions blare, and hard drives spin.

One by one, we arrived in a slow generational retreat from the world we once knew. To build our new city, we mined the old ones instead of virgin ground. We dismantled the fabric of our lives to recast them into new constellations.

The invisible lines that once divided up the world have faded beneath the trees. Planet City is after geography, beyond jurisdiction. The ghosts of nation-states give way to neighborhoods, formed around shared cultural practices, as we perform new stories and myths of care, belonging, and re-creation.

A continuous festival procession dances its way through the city on a 365-day loop. Each day, it intersects with another carnival, culture, or celebration, changing the beats as it goes, endlessly cycling through new colors, costumes, and cacophonies.

The planet is a building. Architecture is a geologic force. Across our history, we have remade the Earth, from the scale of the cell to the tectonic plate. Sheer cliff walls now mark the edge of our new, concentrated city. Everything beyond is rewilding in our wake.

Liam Young is a speculative architect, director, and BAFTA-nominated producer who operates in the spaces between design, fiction, and futures. Described by the BBC as “the man designing our futures,” his visionary films and speculative worlds are both extraordinary images of tomorrow and urgent examinations of the environmental questions facing us today. As a worldbuilder he visualizes the cities, spaces, and props of our imaginary futures for the film and television industry and with his own films he has premiered with platforms ranging from Channel 4, Apple+, SXSW, Tribeca, the New York Metropolitan Museum, The Royal Academy, Venice Biennale, the BBC and the Guardian. He has taught at the Architectural Association, MIT, Princeton University, and now runs a Masters program in fiction and entertainment at SCI-Arc in Los Angeles.