By the end of March, I was in the same boat as everyone else. Or maybe separate boats on similar waters—e.g. remembering to unmute myself on Zoom, stockpiling nonperishables, and wasting any leftover time looking absentmindedly out of my apartment window, wondering what the end of everything will look like when it finally comes. While restaurants closed and dispensable architecture instructors were sent home in the final weeks of March 2020, a few essential services soldiered on. Among the healthcare workers and grocery employees deemed necessary was a curious building project happening just outside the same apartment window—the construction of the very first 5G cellular tower I had seen in the wild.

As it would turn out, this experience was also not particularly unique—the warm weather that accelerated the spread of Covid-19 in the spring of 2020 also marked a return to an ongoing nationwide infrastructural project dubbed the “5G rollout.” Much like myself, many Americans first encountered Covid-19 and the infrastructure of 5G simultaneously. And, like many coincidences, the simultaneity bore an uncanny resemblance to a conspiracy. But before the theory, the simple facts.

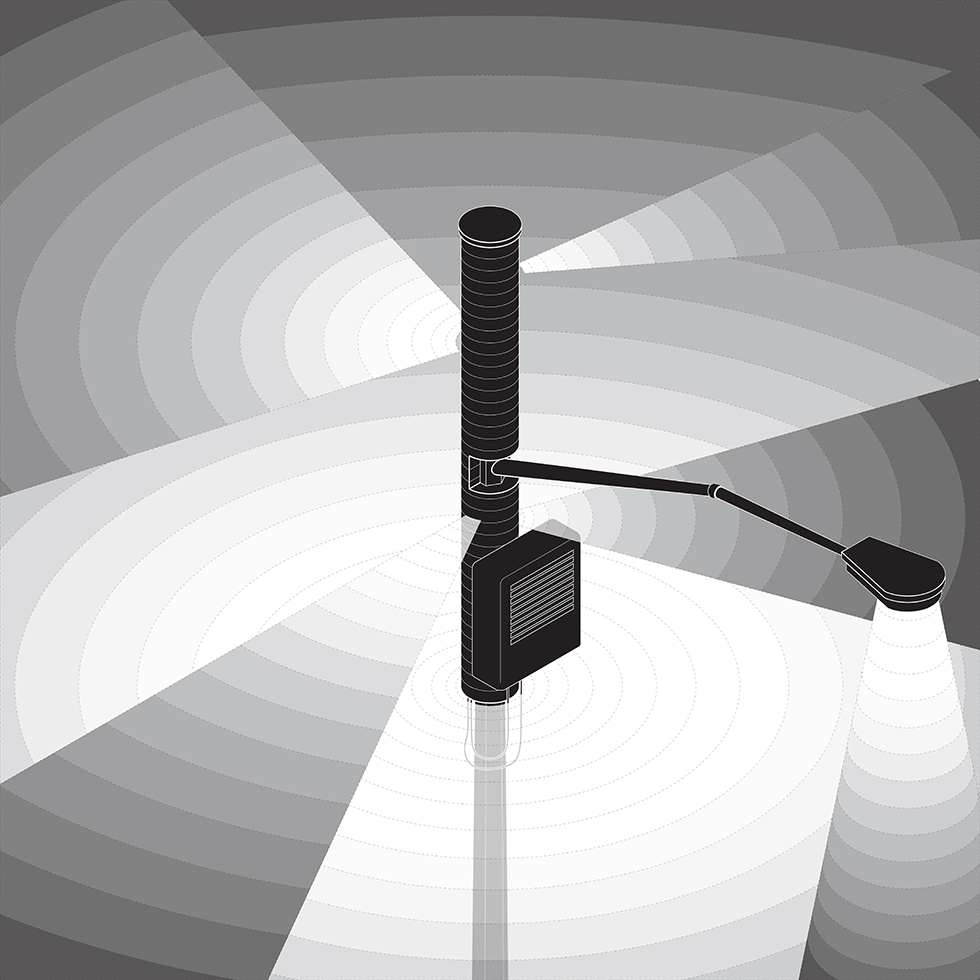

Introduced in 2016, and first deployed in 2019, the fifth generation of mobile broadband (5G) will likely be the dominant cellular network in most countries in the world by the time you’re reading this text.1 5G promises a thousand-fold increase in traffic speeds over the 4G networks that currently comprise most of the United States’ cellular infrastructure. This massive increase in speed is accomplished both by expanding the usable cellular spectrum to higher frequency radio waves and through technological innovations such as beamforming. Where conventional cellular towers broadcast a dispersed signal radiating in all directions, beamforming allows 5G towers to target signals to specific devices at particular times.2 While the general public is generally hazy on technical details like these, the ongoing 5G rollout is evangelized to consumers through peculiar promises like the ability to download an HD movie to your smartphone in under a second.3 And while I might wonder what I’d do with that many movies, or that many free seconds, the market seems more confident. In 2017, an IHS Markit report claimed that the increased speeds associated with 5G cellular networks will generate an estimated $12.3 trillion in global economic activity.4

In a roundabout way, these $12.3 trillion were not only the justification for 5G rollout’s “essential service” designation amidst a global pandemic but ultimately, for the particular tower being built outside my apartment window in Columbus, Ohio. Due to the shorter wavelengths of 5G signals, capturing our stake in the promised trillions will require an almost unimaginable increase in the density of cellular infrastructure. For the millimeter waves of 5G technology, obstacles like trees, walls, and even windows pose a far more significant impediment to signal fidelity than the longer wavelength signals of 4G technology. Where conventional 4G cellular towers have a broadcasting range of about 16 kilometers, 5G towers are most effective at ranges under 300 meters.5 The difference between these distances is not merely one of degree but of type. Whereas the 16-kilometer range of 4G cellular towers allows them to be effectively hidden in the forgettable junk-space of big box parking lots and highway interchanges, the density required of 5G infrastructure will necessitate its intrusion into decidedly less invisible spaces, like my dead-end street in a quiet residential neighborhood in Ohio.

So, while I watched the tower being built, the coincidence of a global pandemic and a global infrastructural upgrade were suddenly joined together in my mind—two things twisted up into a singular experience. I wondered to myself when this next generation of signal would begin permeating the private interior of my apartment, while I wondered when the virus would enter the private interior of my respiratory system. As it would turn out, I wasn’t alone in my conflation of cells with viruses. But before the theory, the simple facts.

Voice-to-Skull

In 1960, a young biophysicist named Allen Frey was working in General Electric’s Advanced Electronic Center at Cornell University when he was visited by a radar technician from a remote corner of the laboratory who’d developed the peculiar ability to hear the radar signals he was supposed to be monitoring telemetrically. Frey visited the stranger’s workstation and, to his surprise, discovered that he too could hear the barely audible clicks and buzzes reported by the technician as the radar oscillated through its frequencies. The observation would become known as the “Frey Effect.”6 Or in other words, the discovery that microwave pulses at precise wavelengths precisely fry the brain. As the brain cooks and cools it expands and contracts, placing pressure on the cochlea in ways that resemble auditory vibrations. Scientists call it a thermo-elastic expansion of the auditory apparatus, allowing subjects to hear what sounds like sounds that have bypassed the eardrum altogether. Higher cooking temperatures soon led to higher auditory resolution. By 1975, deep-fried researchers at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research were able to decipher nine out of ten words through unevenly cooling brains in a method the public would eventually call Voice-to-Skull communication, or V2K for short.

Since its Cold War discovery, Voice-to-Skull has become something like conspiracy Tupperware. A free-floating technology, both technically plausible and terrifying enough to contain a loose array of unrelated conspiracy narratives—from Soviet psychotronic warfare to Freemason mind control campaigns. But Voice-to-Skull’s popularity isn’t just the result of its technical plausibility, V2K’s allure as a container for a half-century of conspiracy narratives stems from its ability to conjure a specific type of terror that underpins the conspiratorial mode itself—the noir terror of private insides turned out; of suddenly doubting the clean partitioning of one’s mind from the world it occupies. With V2K, the skull’s interior is annexed as broadcasting infrastructure within an unimaginably vast telecommunications network. In bypassing the sensory threshold of the ear, your thoughts are no longer yours alone. And like so many other conspiracy theories since its discovery eighty years ago, V2K would quickly prove to be a useful container for growing anxieties surrounding the rollout of 5G cellular technology.

In January 2019, popular Christian conservative YouTuber Dana Ashlie released an interview with an unnamed, unseen, and possibly non-existent former Department of Homeland Security employee who claimed the United States’ 5G rollout signaled the nationwide expansion of a long-running clandestine V2K program.7 The video has been seen over a million times, and the story soon mushroomed on a host of adjacent right-wing internet conspiracy communities. Proponents of Ashlie’s theories noted that the 300-meter effective range of 5G infrastructure corresponded to Frey’s observation that his eponymous effect is most distinct at exactly the same range. Much was also made of the potential usefulness of 5G’s beamforming capabilities in targeting the specific skulls of particular individuals. According to Ashlie and her anonymous guest, the conspiracy entailed unnamed deep-state agents, piggy-backing nefarious sub-2GHZ frequencies atop the innocuous 24GHZ frequencies of standard 5G signals all for the purposes of global mind-control in cul-de-sac-scaled cells—much like the one outside my window.

As a general rule, the internet is somewhere you can find someone who believes in anything. In the months following Ashlie’s interview, the connection between 5G and V2K proved to be particularly popular. By the summer of 2019 it had migrated from niche platforms like 4chan to mainstream social media sites like Twitter. And by the time vague rumors of Covid-19 began to circulate across the United States, consumer electronics retailer Best Buy had already sold out of handheld spectrum analyzers and amateur investigators were mapping the relationship between detectable sub-2GHZ frequencies and the expanding network of 5G towers across American cities.

The funny thing about conspiracy theories is that, like 5G, they also operate through cellular logic. The success of a theory doesn’t depend on the truth of any one particular claim, as much as it depends on the density of inferred connections between those claims. By the time telecommunications experts were appearing on major news television programs to point out the obvious impossibilities of a nation-scaled Voice-to-Skull program, V2K theories were already enmeshed within a dense network of parallel 5G narratives. These disparate theories included everything from the potential for sub-millimeter wavelengths to cause cancer, to accounts of a disputed condition called Morgellons disease, in which individuals believe barely visible nanofibers cultivated by 5G signals within their bodies are emerging through the pores of their skin, like plants towards the light.8

What threads these unrelated narratives together is precisely the fear that 5G compromises the autonomy of the self—that the private interiors of our bodies, our homes, and our neighborhoods have suddenly been turned into transmission nodes within a vast cellular network. Understood in these terms, what appears to be the purely coincidental conjunction of Covid-19 with the 5G rollout is in fact the same fear I felt on my couch in the spring of 2020. Namely, that my insides might not be mine after all. Within weeks of its first outbreak in the United States, anti-5G activists seemed to intuit the paranoid intersection of the virus with emerging cellular technologies. WIRED magazine identified a Belgian doctor named Kris Van Kerckhoven as the first to link Covid-19 with 5G technology.9 On 22 January 2020, in an interview with a Belgian newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws, Van Kerckhoven claimed that while he had not fact-checked the theory, “5G was potentially life-threatening, and no one knows it.”10 In reference to rumors of a quickly spreading Covid-19, and Wuhan’s status as a global leader in the production of 5G technology, he claimed ominously that 5G signals, “may be a link with current events.” Het Laatste Nieuws pulled the story within a few hours and was quick to issue an apology, but the paranoid connection had already been made. The theory spread something like a virus, while the virus itself spread like a cellular network. On YouTube, commentators and vloggers quickly began reporting the “truth” of a clandestine connection between Covid-19 and 5G infrastructure.

By April 2020, the theory had gone IRL. International news reports observed the peculiar presence of anti-5G signage at local lockdown protests from the United States to Australia. Activists decried mask mandates and lockdown orders as violations of their personal autonomy and their right to free association, a narrative that seamlessly mingled with 5G activists’ concerns over the purported effects of millimeter waves on the private interiors of our bodies.11 This strange congealing of 5G paranoia with the public’s anger over lockdown orders soon turned violent. First documented in the United Kingdom, scores of 5G towers were burned across Europe, Australia, and the United States. But as anti-5G conspiracy theorists grew more violent, their unsubstantiated claims were quickly seen as a liability for the ongoing fight against the 5G rollout happening within more respected political circles.

Urban Autonomy

In 2018, long before the general public was aware of voices vibrating their skulls, the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) unveiled a plan to facilitate the national 5G rollout called “5G Fast.” As the name suggests, the plan was intended to accelerate tower construction by capping the rent that local municipalities could charge the telecom industry to host their cells on public masts, and to cut red tape by requiring cities to approve requests for new 5G antennas within sixty to ninety days. As local municipalities came to understand the aesthetic and financial impacts of such a dense network of infrastructure within their communities, cities like Santa Rosa, California, and Indigenous communities like the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma halted local 5G cell construction. More commonly, larger cities such as San Jose ostensibly blocked the rollout by increasing the cost of rent for telecom companies to install their privately owned cells on public utility masts. 12 By the time Het Laatste Nieuws pulled their inflammatory story linking 5G to Covid-19, powerful telecommunications lobbies, the federal government, and numerous local municipalities were already embroiled in months of complex legal proceedings surrounding the right to access public airwaves.

While conspiracy theories like Voice-to-Skull thrive by entangling themselves in dense networks of tangential rumors, misinformation, and amateur research, legitimate legal questions posed by local community activists quickly became mired in the same paranoid soup of anti-5G conspiracies. Local politicians challenging the telecom industry’s appropriation of public infrastructure through non-democratic processes were soon conflated with fringe activists peddling theories like Voice-to-Skull and Morgellons disease. The more cell towers burned across the United States, the more questioning 5G technologies became a political liability, and the faster 5G infrastructure was rolled out. But in order to mount a legitimate challenge against the ongoing undemocratic allocation of our air, we should imagine ways in which 5G paranoia could be understood as an opportunity, rather than a liability.

On Doubt

Throughout the controversies surrounding 5G at the beginning of 2020, nobody ever asked the obvious question: why would anyone want to download an HD movie to their phone in under a second? While 5G is typically marketed through consumer appeals like faster download speeds or real-time VR gaming, the trillions of dollars in profit promised by the technology doesn’t lie in proceeds from movie downloads, but instead, in actualizing an emerging internet of things. Today’s smart technologies and urban infrastructures mostly communicate through an unreliable patchwork of Wi-Fi, 4G LTE, and Bluetooth protocols. The advent of 5G offers the possibility of a unified protocol for reliable, high-speed communication capable of connecting your smart fridge to your self-driving car and everything in-between. In a 2018 white paper, global accounting firm Deloitte claimed, “5G will expand the network effect dramatically by extending the reach of the Internet to almost any kind of connection.”13

The majority of the smart technologies that we interact with today consist of so-called “Critical IoT” applications. These applications, like Amazon’s Alexa, rely on nearly constant, low-latency connections to facilitate activities that depend on data-rich communication. In distinction to conventional “Critical IoT,” 5G offers the possibility of what machine-to-machine communications corporation Telit describes as “Massive IoT,” a smart regime consisting of billions of low-power, low-cost devices, intermittently transmitting very small amounts of data.14 Massive IoT is not just an internet of things, but an internet of nearly everything. While 5G technology is unlikely to cultivate nanofibers beneath your skin, its profitability lies in transforming the objects that comprise the backgrounds of our daily lives into instruments for collecting, broadcasting, and monetizing information about us.

Theorist Jathan Sadowski likens this emerging internet of things to a process of terraforming. Like the sci-fi geo-engineering of a distant planet, the contemporary terraforming of the city centers upon reengineering our environments in order to make them compatible with new regimes of surveillance that profit off the circulation of user data.15 When economists speak of the trillions of dollars at stake in the 5G rollout, they’re specifically describing the revenue generated by household objects mining our most intimate domestic routines for insights into our future behaviors. Seen in these terms, clandestine Voice-to-Skull networks and totalitarian thought control suddenly seem less outlandish. While the transformation of our domestic interiors into digital surveillance networks may not be vibrating our skulls or cultivating nanofibers beneath our skin, 5G is nothing if not a violation of our autonomy as individuals.

Where the fight against the ongoing 5G rollout and the smart city it will soon facilitate have largely consisted of either legal appeals for a more democratic allocation of public infrastructure or conspiratorial appeals to theories like Voice-to-Skull, both strategies miss the essential fact that the intimate forms of personal data captured by emerging Massive IoT regimes now comprise a new kind of civic infrastructure altogether. Not the material infrastructure of utility masts or EMF cells, but an ever-expanding informational infrastructure consisting of billions of vectors of data, mined from our personal lives by the smart technologies that facilitate them. The rideshare app that knows who’s having an affair or the smart television monitoring the fluctuations in your attention span produce enormously profitable surveillance products, harvested from our private lives.

Rather than raising the rent of public utility masts, or advocating for nostalgic notions of personal privacy, we need to demand a bolder techno-politics, one in which our data would be understood as a new kind of civic commons. In her recent essay “Known Unknowns,” Karina Forrester argued, “Policies to protect privacy appeal to a language of transparency, individual consent, and rights. But they rarely try to disperse the ownership of our data—by breaking the power of monopolies that collect it, or by placing it under democratic control through public oversight.”16 Rather than simply advocating for privacy, surfing with VPN, or lining the insides of our homes with tinfoil, what if the conspiracies surrounding 5G allowed us to imagine a techno-politics of an expanded self. Selfhood that doesn’t stop at the edges of our bodies but extends to include the vast empires of information our lives now generate.

Instead of merely privacy, instead of simply evicting the deep-state from our vibrating cochlea, a techno-politics for an expanded self would regard these networks of user information, like our physical bodies, as another site for self-determination. It would understand the aggregation of these networked selves, like the physical city, as an invaluable shared resource. And, most importantly, it would demand democratic control over how these resources are used, by whom, and to what ends.

Curtis Roth is an associate professor at the Knowlton School of Architecture at Ohio State University. Prior to this he was a resident fellow at the Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart, partner of OfficeUS at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale, and a Howard E. Lefevre Emerging Practitioner Fellow. His work has been published in E-Flux, Thresholds, Volume, and Perspecta, and exhibited at the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, the Venice Biennale, and the Druker Design Gallery.